This post is based primarily on

Don's notes, occasionally supplemented with MT's notes from our Camino in 2016.

When information from other sources is added—for further explanation to readers

or to satisfy our own curiosity—that is set off in a text box (as this one).

Most of the photos that accompany

this post are from Don’s camera (with a caption indicating the time it was

taken); those from MT’s iPhone are indicated by “MT” placed at the beginning of

the photo caption. Photos from any other source (such as the public domain

Wikimedia Commons) indicate that source in the caption.

Friday, September 2, 2016, 8:04 AM – Tomar: Pensão Residencial União – our window with view of tile roofs.

8:05 AM – Tomar: Pensão Residencial União – view of tile roofs from our window.

We

ate the nice buffet breakfast at Pensão

Residencial União and then took down our clothes from the clothesline just

outside the breakfast room.

After

breakfast, we walked to the bus station

and bought tickets for the 5:30 pm bus to Alvaiázere (€3.85 ea).

Then

we walked to Igreja de São João Baptista.

9:17 AM – Tomar: view to W on Rua Serpa Pinto, from Pensão Residencial União (outdoor seating for Café Paraiso on left, Restaurante Tabuleiro on right), with Igreja de São João Baptista and City Hall at end of street.

We

got the first (of 4) carimbos that

day at Igreja de São João Baptista.

Tomar: carimbo stamp from “Paroquia Tomar” (Parish [Church] of Tomar) with Cross of the Order of Christ.

10:06 AM – Tomar: Igreja de São João Baptista –

tower and façade.

The Igreja

de São João Baptista (Church of St. John the Baptist) is a 15th-century Catholic

church that was built by King Manuel I and is of Manueline

architecture. However, it also incorporates Gothic and Baroque elements. It has

been classified as a National Monument since 1910.

There has been a place for meeting and

worship on this site since the time of the Knights Templar in the 12th century.

Only two portals remain from the older Gothic church, which was also dedicated

to St. John the Baptist. The present building largely dates back to the late

15th and early 16th century, when the church was rebuilt in the late 15th

century by Henry the Navigator and then expanded by King Manuel I in the early

16th century. The symbols associated with Dom Manuel (the royal coat of arms,

the armillary sphere, and the Cross of Christ) are seen in the tower, the north

and south portals, and again in the pulpit.

The church, and in particular its façade

and grand entrance door, is an important example of Manueline architecture. It

has been restored and renovated several times since 1875. Throughout the 20th

century, the church was the subject of a succession of cleaning and restoration

works.

This main church of Tomar is located in the

main square of the town (Praça da República), in front of the City Hall (17th

century) and a modern statue of Gualdim Pais.

It is flanked by the two oldest streets of Tomar, Rua Serpa Pinto and Rua de

São João (Street of St. John).

Altough this church served for many years—perhaps

centuries—as the “igreja paroquial de Tomar” (parish church of Tomar), the

truth was that the only religious parish was Santa María dos Olivais. The Igreja

de São João Baptista assumed this function because it was the most central

church and also due to the poor condition of Santa María, which was not used

for worship. São João Baptista had long been a civil parish (frequesia), but only in 1993 was it officially

elevated to the status of a religious parish (paroquia).

10:06 AM (Cropped) – Tomar: Igreja de São João

Baptista – Manueline door.

The Manueline

portal of the main façade features an arch with contra-curved archivolts

surmounted by an alfiz decorated with

reliefs of plant motifs and zoomorphic (animal) and heraldic symbols (the royal

coat of arms, the armillary sphere, and the Cross of Christ).

The photo of the Manueline portal Don had taken the evening before better shows the details of its decoration.

Thursday, September 1, 2016, 9:14 PM – Tomar: Igreja de São João Baptista –

Manueline main portal (no flash, at night).

To the left of the main façade is the 16th-century Manueline clock tower, with a quadrangular base, an octagonal top section

with openings for bells on all 8 sides and the clock, and a hexagonal pyramid

spire. By order of King João III, the clock face (decorated with faces and

skulls) was transferred to the church in 1523 from its original location on the

Porta do Sol (Sun Gate) of the

Castelo de Tomar.

Tomar: Igreja de São João Baptista – Manueline clock

tower: octagonal top section with bells and clock; and top of quadrangular

lower section with the royal coat of arms, the Cross of Christ, and the

armillary sphere (en.wikipedia.org).

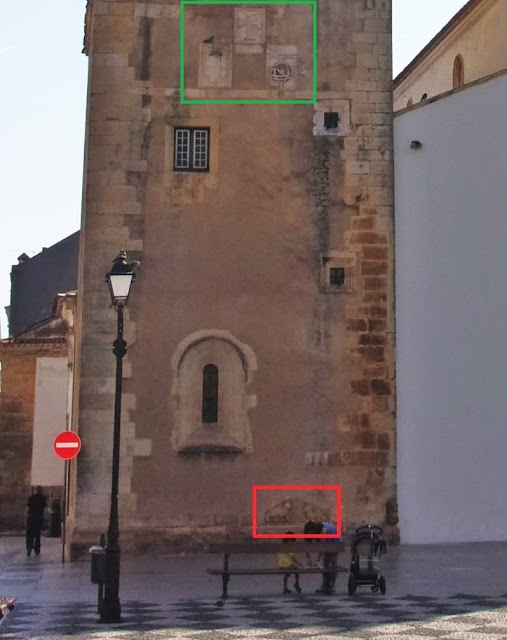

Friday, September 2, 2016, 10:06 AM (Cropped, Paint) – Tomar: Igreja de São

João Baptista – quadrangular base of tower with the royal coat of arms, the

Cross of Christ, and the armillary sphere at its top (see green rectangle) and

sculpture at bottom right (see red rectangle).

Thursday, September 1, 2016, 9:18 PM – Tomar: Igreja de São João Baptista –

sculpture low on wall left of main portal (no flash, at night).

At the base of the tower, to the left of

the façade, there is a trapezoidal

fragment of carved stone, perhaps originating from an old tympanum, carved

in relief, with two lions em cortasia

[in courtesy] flanking flowered branches (representing the Tree of Life). Some

sources call the animal at the left “a prominent dog.” Other sources, citing an

a similar old image of a dog and lion flanking a long stem topped by a

fleur-de-lis, see the animal on the right as a lion (representing the Lion of

Judah or the constellation of the Lion) and on the left a dog (representing the

constellation of the Greater Dog or possibly the Templar Order, whose knights

were known as Domine Canes, meaning

The Lord’s Dogs, or Guardians of the Faith).

This stone probably came from the former

Igreja de Santa María do Castelo, and may have been brought from Jerusalem by

Dom Gualdim Pais. When the old church was destroyed, this stone was forgotten

in its crypt, but was later placed in the tympanum of the main door of the

original Igreja de São João Baptista. Documents indicate that, when the latter

was dismantled in order to construct the present Manueline church, the

16th-century master builder of its replacement had “orders to remove the stone

lions and toss it in pieces into the rubble of the new floor of the base the

church tower,” but he saved this “Templar slab by placing it under thick

plaster on the outside of the tower base.”

Friday, September 2, 2016, 9:20 AM – Tomar: Igreja de São João Baptista –

interior, view from rear to apse, pulpit at left, with MT in aisle.

The interior

of the church is distinguished by the pulpit with symbols of King Manuel I, the

decorated capitals of the inner columns of the nave and several panels

painted in the 1530s by one of Portugal's best Renaissance artists.

17th-century diamond-point azulejo

tiles cover the inside walls of the apse.

Tomar: Igreja de São João Baptista - pulpit with coat of arms and armillary

sphere of Manuel I (commons.wikimedia.org).

In

front of this church was the Praça da

República.

9:19 AM – Tomar: Praça da República with statue of

Gualdim Pais and City Hall, Castelo de Tomar in hill behind it.

10:06 AM – Tomar: Praça da República with statue of

Gualdim Pais, with City Hall in background. Inscription on pedestal of statue:

“A D. Gvaldim Pais Fvndador de Thomar 1160-1162-1938” (To Dom Gualdim Pais

Founder of Tomar, 1160-1162-1938); inscription on base of pedestal: “1162 –

Tomar – 1962, No VIII° Centenário da

Outorga do 1° Foral a Cidade

de Hoje Rende Homenagem ao Seu Fundador, C[oncelho].M[unicipal].T[omar]” (1162

– Tomar – 1962, On the 8th Centenary of the Granting of the 1st Charter to the

City That Now Pays Homage to Its Founder, Municipal Council of Tomar).

Dom

Gualdim Pais

(1118-1195) was a Portuguese crusader, Knight Templar in the service of Dom

Afonso Henriques of Portugal, and founder of the city of Tomar. He was born in

the town of Amares, near the Portuguese city of Braga. During the Reconquista, he fought alongside Afonso

Henriques against the Moors, and was knighted by him in 1139. Shortly

thereafter, he departed for Palestine and, for 5 years, fought there as a

Knight Templar. In 1157, he became the fourth Grand Master of the Order of

Knights Templar in Portugal, which at that time was ruled from Braga. In 1160,

he founded the Castelo de Tomar (Castle of Tomar), which was then near the

frontier with the Muslim states that still occupied part of Portugal, and

transferred the seat of the order there. In 1162, he issued a foral (feudal charter) that established

the town of Tomar. The famous Round Church of the Castle of Tomar, inspired by

similar structures in Jerusalem, was built under his supervision.

In 1190, Moorish forces attacked

Tomar and surrounded the castle. Although greatly outnumbered, the crusader Knights,

led by 72-year-old Gualdim Pais, kept them at bay. A plaque commemorates this

bloody battle at the castle’s Porta do Sangue (Gate of Blood).

Gualdim Pais died in Tomar in

1195, and is buried in the Igreja de Santa María do Olival in that city.

Before

starting our way up to the Castelo de Tomar/Convento de Cristo, we visited the Convento de São Francisco (Monastery of

St. Francis), where we again got carimbos.

Tomar: carimbo stamp from “Ordem Franciscana Secular – Fraternidade de

Tomar” (Secular Franciscan Orden – Fraternity/Brotherhood of Tomar) with Tau

symbol.

9:53 AM – Tomar: Convento de São Francisco – façade

and tower.

The Convento de São Francisco (Monastery of St. Francis) dates from the

17th century. It is a typical example of Mannerist architecture, with a single

nave covered by a high barrel vault. The 17th-century building replaced the Capela

de Nossa Senhora dos Anjos (Chapel of Our Lady of the Angels).

The convent (monastery) was

founded in 1624 by a community of Franciscan monks, and construction of the

church began in 1628. The main body of the church was completed in 1636, and

the tower to the right of the façade was completed in 1660. The main façade

consists of 3 panels, the center of which has 3 floors. The top of the façade is

cut in “successive Mannerist ripples,” the bottom level of the center section

is interrupted by a Mannerist portal with a curved pediment, and the remaining

space of the façade features several windows divided on 2 floors and “grouped

as a large barn.” The convent cloister is located to the left side of the

building.

After the abolition of religious

orders in Portugal, the convent was turned over to the Ministry of War, which

installed a military battalion there. Currently, the protection of the building

is divided between the Third Order of St. Francis, which owns the property, and

the City of Tomar, which is responsible for the grounds and the remaining

space.

9:39 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo, view from below, near Convento de São Francisco (telephoto 186 mm); the

tallest tower is the Torre de Menagem (Keep); the shorter tower to the left is

the Torre de Dona Catarina.

Reportedly, from the Torre de

Dona Catarina, there was a staircase in this tower leading to a tunnel for

access to the city.

The

Castelo de Tomar/Convento de Cristo

was up many (switchback) steps and cobbled paths zigzagging up the hill.

9:53 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo, view from below, just before we started up to it; showing some of the

round towers of the outer wall and the quadrangular towers (Torre de Dona Catarina

and Torre de Menagem) (telephoto, 112 mm).

The Castelo de Tomar (Castle of Tomar), also known as Castelo dos

Templarios (Castle of the Templars), has a long history. Dom Afonso Henriques

gave the Knights Templar the responsibility for the defense of lines that led

to Coimbra, the capital of the Kingdom of Portugal during the 12th century. In

this process, the Templars came into possession of a vast territory, between

the Tejo and Mondego rivers, whose purpose was to control the southern access

to Coimbra and whose center was precisely at Tomar. The royal charter of the

gift dated from 1159, and the castle began to be built a year later, in 1660,

according to the inscription that is preserved in the keep. Gualdim Pais, Grand

Master of the Templars at that time, was the main overseer of the construction

of the castle, considered one of the largest examples of defensive architecture

in Portugal. The Castle of Tomar became an integral part of the defensive

system created by the Templars to secure the border of the young Christian

Kingdom of Portugal against the Moors.

However, the origins of the

castle must have been prior to this bestowal. Several authors have drawn

attention to vestiges that prove the previous existence of a military

structure, the contours of which are not still well defined, but which can go

back to the Roman epoch and had continued in the Islamic period.

The Castle of Tomar was built on

a strategic location, atop a hill and near the River Nabão. It has an outer

defensive wall and a citadel (alcáçova)

with a keep inside. The keep, a central tower of residential and defensive

functions, was introduced in Portugal by the Templars, and the one in Tomar is

one of the oldest in the country. Another novelty introduced in Portugal by the

Templars (learned from decades of experience in Normandy, Brittany, and

elsewhere) are the round towers of the outer walls, which are more resistant to

attack than traditional square towers.

Despite many changes in the

fortified enclosure, most of them related to the successive campaigns of

expansion of the Convent of Christ, the Romanesque elements of the fortress are

still numerous and significant. The most important is the keep, of a

rectangular footprint; it rises in three floors, well above the walls that delimit

the alcáçova. Below this upper

enclosure is a wider space that initially corresponded to the fortified village

of the Middle Ages. It was not until 1499, by order of King Manuel I, that the

population inside the walls was forced to move to the village next to the

river. The remains of some of the residents’ dwellings are located within the

outer walls of the castle.

Over the centuries, the site was

occupied by multiple buildings, in particular by the whole Convent of Christ.

The Romanesque Charola (Round Church),

built in the transition to the 13th century, was implanted in the west section

of the castle and, from then on, a series of new spaces and structures were

added.

As

we arrived at the top of this long climb, there was a sign about the Castle and

Convent.

10:17 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo, sign by entrance – English part about “Templars Castle”:

“The

fortress of Tomar, founded by D. Gualdim Pais in 1160[,] was to give strategic

support to the Christian advance southwards and was the seat of the Order of

the Temple.“Absorbing the structures of an Islamic population nucleus from the 9th to the 12th centuries[,] the Templar fortress of Tomar was organised into three large spaces clearly bound by walls.

“The fortification of Tomar made use of solutions which were extremely modern for their time [,] some of which had already been tried in military architecture in the Holy Land, where Gualdim Pais had stayed for five years.

“The Romanesque oratory, with its central plan, was also inspired by the distant Temple of Jerusalem.”

10:17 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo, sign by entrance – English part about “Convent of Christ”:

“The

Order of the Temple was abolished in 1312. In Portugal its property and part of

its vocation would be inherited by the Order of Christ, created at the request

of D. Dinis.“With the frontiers of the country strengthened, a new military and religious order played an important role in overseas expansion. The gradual need to adapt the new Order to social changes brought about successive spiritual reforms. The alteration would mean various building contracts being carried out.

“After the abolition of religious orders in 1834[,] ownership was partly transferred to António Bernardo da Costa Cabral. The private residence of the Marquis and Count of Tomar was reacquired by the state in 1933.

“In 1983 the Convent of Christ was classified as a World Heritage monument by Unesco along with the Templar castle.”

We

entered the complex through the Porta do

Sol gate in the outer wall of the Castelo de Tomar.

10:18 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo - part of wall (with alambor) and

path leading to entrance.

An alambor is an incline

built at the base of the wall to keep siege engines at bay and cause

projectiles to bounce.

10:21 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Don and MT on path leading to entrance.

10:21 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Don and MT on path leading to entrance (telephoto 64 mm).

10:19 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Porta do Sol (Sun Gate) gateway where we entered through the castle

wall.

10:23 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – MT by Porta do Sol (Sun Gate), with part of formal garden inside gate.

10:23 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – sign before entrance with diagram of the layout of Castelo dos

Templarios (Templar Castle) and text in English and Portuguese.

10:23 AM (Cropped) – Tomar: Castelo de

Tomar/Convento de Cristo – top part of sign before entrance with diagram of the

layout of Castelo dos Templarios (Templar Castle) with callouts (labels) in Portuguese

and English.

10:23 AM (Cropped) – Tomar: Castelo de

Tomar/Convento de Cristo – bottom part of sign before entrance; English part of

text:

“Founded

in 1160 by D. Gualdim Pais, as the headquarters of the Order of the Knights

Templar, the castle absorbed part of a Muslim settlement dating from the

9th-12th centuries.“The fortified structure shows Middle Eastern influences new to Portugal, such as the Keep and the alambor, a reinforcement incline built at the base of the wall to keep siege engines at bay and cause projectiles to bounce. The original wall included the Alcáçova – from the Arab Alkasaba, meaning fortress with royal residence – the quarters exclusive to the Knights Templar; the Almedina, the central, usually fortified part of the town; and the Oratory, in the shape of a rotunda. When the Order of Knights Templar was disbanded in 1319, the castle was transferred to the Portuguese Order of Christ, becoming its headquarters in 1357.

“New buildings were erected in the 16th century, during the large work campaigns ordered by King Manuel and King João III, occupying an inhabited area known as the ‘arrabalde de S. Martinho’.”

Once

inside the castle wall we headed toward the Convento de Cristo.

The church and chapter house of

the Convento de Cristo (Convent of the Order of Christ) at Tomar (designed by diogo de Arruda ) is a major

Manueline monument. (See Appendix B of this blog for more information on the

Manueline style.) However, the castle and convent have examples of Romanesque,

Gothic, Manueline, and Renaissance architectural styles—a combination of the

architectural and artistic styles of several centuries.

Tomar: Convento de Cristo –

Floorplan of the Church and Chapter House of the Convent of Christ; the Templar

Charola (round church, late 12th

century) is indicated in red, and the Manueline nave and chapter house (early

16th century) are in blue; the addition made by Henry the Navigator (15th

century) is in green (en.wikipedia.org).

The Order of the Poor Knights of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon (Latin Ordo Pauperum Commilitonum Christi Templeque Salomonici), known as the Knights Templar, was created in 1118, in the aftermath of the First Crusade of 1096, with the original purpose of protecting pilgrims making the pilgrimage to Jerusalem after that conquest. Although it was a military order, its members took a vow of poverty to become monks. The Templar name comes from the place where the order originally settled, on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, where the Temple of Solomon had been. When the Holy Land was lost, the Templars returned to Europe, and Portugal was the first country in which they settled, arriving in 1128. From 1160, the Order established its headquarters in that country in Tomar. The Castle of Tomar, whose construction began in that year, served as the convento (monastery) for the warrior-monks. Its construction continued until the final part of the 12th century, with the construction of the oratory (known as the Charola, Rotunda, or Round Church), in one of the angles of the castle, completed under the guidance of the Grand Master Dom Gualdim Pais.

Following the dissolution of the Templar Order in the 14th century, Pope John XXII (following the request of King Dinis of Portugal) instituted the Order of Christ, which inherited the Templar territories in Portugal, and many of the former Templar knights joined the new order. In 1357, the seat of the former Knights Templar in Tomar was converted into the seat of the Order of Christ. As a result, around the first half of the 15th century, work was completed to adapt the Templar oratory, introducing an open choir to the western niche, about halfway up the wall. What remains of this adaptation was a colonnade frame with interior arch. At the same time, the main palace was constructed.

Infante Dom Henrique, o Navegador

(Prince Henry the Navigator, 1394-1460) became the administrator of the Order of

Christ in 1420, and he used its resources to launch his expeditions. The

refurbishment of the complex at Tomar reflected the newfound wealth and success

of Henry´s explorations, and it is now one of Portugal´s world heritage sites.

The Cross of Christ was the emblem adorning the sails of the Portuguese ships

that roamed the seas.

During the time of Henry the

Navigator’s leadership of the Order of Christ (1417-1460), the Order initiated

the construction of two cloisters: the Claustro do Cemitério (Cemetery

Cloister) and Claustro das Lavagem (Washing Cloister). Prior to these large

works, Henry began constructing the Capela de São Jorge (Chapel of St. George)

sometime in 1426.

In 1484, Dom Manuel (who became

Master of the Order in 1484 and King Manuel I of Portugal in 1492) ordered the

construction of a sacristy (today the Hall of Passage) that connected the choir

to the Capela de São Jorge, linking the choir with the wall of the stronghouse

(keep). By the end of the 15th century, the convent’s General Chapter decided

to expand the convent (sometime around 1492): the Chapter House, main altar,

ironworks for the niche/archway, paintings and sculptures (for the same), and

the choir were all expanded or remodeled.

In 1503, the old Vila de Dentro

was expropriated within the walls, and the Sun Gate and Almedina Gate were

closed. By 1506, Dom Manuel ordered the construction of the church’s nave.

Thus, Dom Manuel, as King and also Governor of the Order of Christ, extended

the church to the west with new construction outside the walls of the castle,

with decoration celebrating Portuguese maritime discoveries, the mystique of

the Order of Christ and of the Crown in a great manifestation of power and

faith.

The successor of Manuel I, King

João III, demilitarized the Order of Christ, turning it into a more religious

order with a rule based on that of Bernard of Clairvaux. João III declared that

all the monks of the Order would have to live in the convent and transformed

the convent into a thoroughly monastic community. Starting in 1531, he built

the grandiose Renaissance convent, against the west flank of the castle and

surrounding the Manueline nave. This expanded area, adding dormitories,

refectory, kitchen, and cloisters, is known as the Convento Joanino (Joanine

Convent). It also included an aqueduct around 6 km long for water supply.

The Castelo Templário/Convento de

Cristo (Templar Castle/Convent of Christ) was the headquarters of the Knights Templar

until 1314 and of the Ordem de Cristo (Order of Christ) from 1357. From the

castle (1160) is part of the octagonal rotunda (the end of the 12th century),

the Romanesque sanctuary of Eastern influence. The Rotunda (Round Church), the

Chapter window, and the Cloister of King João III are the high points.

10:24 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – main building (Round Church) of Castle/Convent, with more convent area

to left and tour entrance at top of steps and around corner to right.

10:23 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – main building (Round Church) of Castle/Convent, with convent area to

left and tour entrance at top of steps and around corner to right; part of

formal garden and castle wall to right.

10:25 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – main building (Round Church) of Castle/Convent, with church’s

Manueline nave to left rear and tour entrance at top of steps and around corner

to right.

MT 10:33 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Don on steps up to main building of Castle/Convent, the Charola or

Rotunda (Round Church).

10:25 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – view back through formal garden to Porta do Sol (Sun Gate).

10:27 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – ruins of Igreja de Santa María do Castelo (Church of St. Mary of the

Castle).

Santa

María do Castelo

was an old freguesia (civil parish)

in the city of Tomar, which included the alcáçova

(citadel) and the almedina (fortified

part of town) on the hilltop of the Castelo. It was here that a primitive

village developed inside the wall. In the 16th century, the prior Friar António

de Lisboa undertook a reform of the Order of Christ to make it into a

cloistered order, as dictated by King João III. To this end, all the houses

located inside the wall were destroyed, in order to allow the expansion of the

Convento de Cristo. The inhabitants were moved to the Vila de Baixo (Lower

Village). The paróquia (parish) was

abolished and incorporated into that of São João Baptista. The parish church, Igreja de Santa María do Castelo

(Church of St. Mary of the Castle) was built inside the walls of the Castelo de

Tomar and completed around 1176. It was located near the Porta do Sol (Sun

Gate), immediately to the left of the gate.

10:28 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Portal Sul (South Portal); ornate door to left of Castelo tourist entrance.

The entrance to the church is through a magnificent lateral portal,

from around 1515-1530. The Charola originally had its entrance facing east; it

was the works of Dom Manuel I that established a new entrance on the south side

of the enlarged church.

The Porta Sul (South Portal) takes advantage of the thickness of the

church wall to create an architectural canopy on top and protect the sculptural

group, which included several symbolic figures of prophets of the Old Testament,

mitred clergy, Doctors of the Church (Saints Jerome and Augustine on the left, Saints

Gregory and Ambrose on the right), with the image of the Virgin Queen of Heaven

(with Child) in the center and the Cross of Christ at the top. It is also

decorated with abundant Manueline motifs. From a stylistic viewpoint, it is a

merger between the Manueline and the Gothic, already influenced by the decorative

lexicon of the Renaissance, through the Plateresque ornamentation widespread in

Spain.

Tomar: Convento de Cristo – Porta Sul entrance of the Convent church in Manueline style (en.wikipedia.org).

The South Portal was the work of the architect João de Castilho (1470-1552), during his first period of work on the Convent (1513-1515), still influenced by the Manueline taste of his predecessor Diogo de Arruda. He designed it as a counterpoint to Arruda’s famous Chapter House Window.

10:29 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – statue of Trinity near ticket counter, in Capela de São Jorge (Chapel

of St. George); sign in Portuguese: “Santíssima Trinidade em Trono de Graça,

Imagem em pedra, polycromda, Inicio de sec. XVI, Proveniéncia Igreja Paroquial

de S. Pedro, Tomar” and English: “Holy Trinity on Throne of Grace], Polychrome

stone image, Begin[ning] of XVI th cent, Origin St. Peter Parish church, Tomar.”

The

price of entrance was €3 ea (50 % off for being over 65).

Tomar: carimbo stamp from "Caminhos de Santiago – Convento de Cristo –

Tomar” with

scallop shell projecting from

the convent.

The self-guided tour, following arrows, took us first to the two Gothic cloisters east of the Round Church.

Two serene, azulejo-decorated Gothic

cloisters to the east of the Charola

were built during the time when Prince Henry the Navigator was Grand Master of

the Order in the 15th century: the Claustro da Lavagem and Claustro do

Cemitério. The Convent of Christ actually has a total of 8 cloisters, built in

the 15th and 16th centuries.

Tomar: Castelo de

Tomar/Convento de Cristo – diagram showing location of Gothic cloisters in

gray: Claustro da Lavagem on right and smaller Claustro do Cemitério on left

(pt.wikipedia.org).

First,

we came to the Claustro da Lavagem

(Washing Cloister).

10:33 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Cloister

of Washing, with azulejo tiles on

lower part of interior walls.

The Claustro da Lavagem (Washing Cloister) is a 2-story Gothic cloister

built around 1433 under Henry the Navigator. Servants used to wash the garments

of the monks in this cloister; hence the name. This cloister affords nice views

of the crenellated ruins of the Templars’ original castle. This 2-story

cloister was originally linked the Claustro do Cemitério with the Paço do

Infante (Palace of the Prince).

Tomar: Convento de Cristo -

Gothic Cloister of Washing, with Charola (Round Church) in background

(pt.wikipedia.org).

10:33 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de Cristo

– view from Washing Cloister: at left, beyond the steps that had led us to the

entrance, are the ruins of Igreja de Santa María do Castelo.

Next,

we came to the Claustro do Cemitério

(Cemetery Cloister), the second of the two Gothic cloisters east of the Round

Church.

The Claustro do Cemitério (Cloister of the Cemetery) was also built

under Henry the Navigator and dates back to around 1420. This Gothic cloister

was the burial site for the knights and monks of the Order. It contains two

16th-century tombs and pretty citrus trees. The elegant twin columns of the

arches have beautiful capitals with vegetal motifs. The walls of the ambulatory

are decorated with 16th-century tiles.

Tomar: Convento de Cristo - Gothic Cloister of the Cemetery (en.wikipedia.org).

Although neither of us took a photo of the Cemetery Cloister, Don did take one of the sign about it.

10:34 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Sign for Claustro do Cemitério (Cemetery Cloister), with diagram

showing its location (the larger cloister to its right must have been the

Claustro da Lavagem), and text in English and Portuguese; English text:

“Built

by the architect Fernão Gonçalves when the Infante D. Henrique (Prince Henry)

was Governor and Administrator of the Order of Christ (1420-60), it was

remodelled at the beginning of the 17th century (Filipian period). It served as

ground for religious processions and burial of the friar knights [Portuguese

text adds: beneath the pavement of the galleries].“Arcosolia [arched recesses in wall] built in this cloister house the tombs of D. Diogo da Gama († 1523), Baltazar de Faria († 1584) and Pedro Álvares Seco de Freitas († 1599).”

Continuing

to the west, we came to the Sacristía

Nova (New Sacristy).

10:42 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – sign for Sacristía Nova (with name at top cut off, but diagram showing

it to left [west] of Claustro do Cemitério) with English and Portuguese text;

English text:

“Built

in the late 16th century by the Master of Works of the Convent, Francisco

Lopes, during the priorship of Friar Adrião Mendes (1575-78), it was also [Portuguese:

In this location previously functioned] the Chapter House in the time of Prince

Henry (15th century).“Work to unify the style was carried out in 1629-30, under the direction of Diogo Marques Lucas, architect of the Order of Christ.

“The vaulting decoration, dating from the time of the Spanish Philips [17th century] displays a new Cross of Christ, the armillary sphere and the royal [coats of] arms.”

10:42 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – vaulted ceiling of Sacristía Nova; of the 4 prominent panels in the

center, the 2nd from left is an armillary sphere, the 2nd from right is Cross

of Christ; other 2 are coats of arms.

10:42 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – vaulted ceiling and walls of Sacristía Nova.

The Sacristía Nova (New Sacristy) or Sacristía Filipina (Sacristy of

the Filippo school), to the northeast of the Charola (Round Church), is between

the Claustro do Cemetério and the Sala de Passagem (Hall of Passage). It was

designed by Francisco Lopes in the late 16th century. It replaced the old Sacristía

de São Jorge (Sacristy of St. George), from 1484, which is the present Hall of

Passage. In 1615, Diogo Marques Lucas, a disciple of the Italian architect

Filippo Terzi, was appointed Master Builder of the Convent, and he remodeled

the sacristy in 1620.

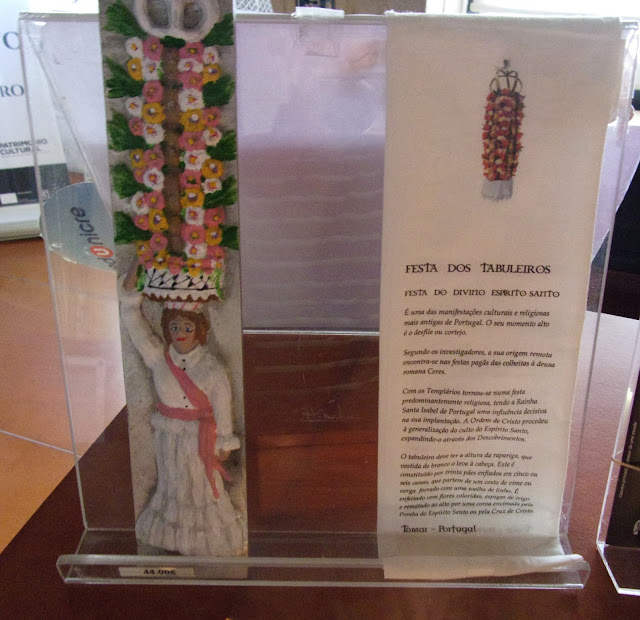

10:45 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – poster (?) about Festa dos Tabuleiros, with price of “44.00€” at

bottom left of plastic holder.

Then

we came to the Charola or Rotunda (Round Church).

10:47 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – central drum of Round Church (view from nave, through arch).

The Romanesque Rotunda (Round Church), also known as

the Charola,

was originally built in the second half of the 12th century by the Knights

Templar as the chapel of the Castelo de Tomar. From the outside, the church is

a 16-sided polygonal structure, with strong buttresses, round windows, and a

bell tower. Inside, the Round Church has a central, octagonal structure,

connected by arches to a surrounding gallery (ambulatory). Like several other

Templar churches in Europe, the general shape of the church was modelled after

similar round structures in Jerusalem: the Dome of the Rock (which was believed

by the crusaders to be a remnant of the temple of Solomon) and the church of

the Holy Sepulcher. It is said that the circular design and high ceiling

enabled knights to attend Mass on horseback.

The construction of the Round

Church was carried out in two stages: the initial work took place in the second

half of the 12th century (1160-1190), in a time dominated by the Romanesque;

the second stage, finishing the church, was nearly four decades later (ca.

1230-1250), already under the full influence of the Gothic in Portugal.

Prince Henry the Navigator,

governor of the Order of Christ from 1420 to 1460, would make the first changes

in the Templar Rotunda in order to endow it with the space requirements of the

liturgical functions of a branch of contemplative friars that he introduced

into the Military Order of Christ. For this, he would open two windows on the

side of the two sections of the ambulatory facing west and then open four

chapels on the walls of the ambulatory oriented northeast, northwest,

southeast, and southwest. In the remaining sections, he installed altars

surrounding the ambulatory.

The entrance to the building was

originally from the east, but would be moved to the west in the reign of King

Manuel I, through a triumphal arch connecting it with the Manueline nave that

made the Charola into the chancel (area around the main altar) of the new

church. The arch replaced the two windows of Prince Henry.

Tomar: Convento de Cristo – Round Church, view from the nave through arch (en.wikipedia.org).

Inside the generous ambulatory is

an octagonal central drum of 8 pillars, each composed of four columns. The

capitals of the columns are still Romanesque (end of 12th century) and depict

vegetal and animal motifs, as well as the Biblical scene of Daniel in the Lions’

Den.

In the early 16th century, a wide

arch was opened to the choir, whose light comes from the oculus (circular

window) that on its exterior integrates the decoration of the Chapter Window.

The décor of the rotunda consists of motifs in the central drum structure,

paintings in the dome, murals on the second floor of the drum (representing

instruments of the Passion of Christ), 8 of 14 primitive painted panels in the

perimeter wall, wooden sculptures (representing angels, saints, and prophets)

and a statue of the Virgin with St. John.

10:47 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Round Church, column with statues and paintings of central drum.

10:48 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – sign in English (blurred) and Portuguese for “Freestanding sculpture

at [Portuguese: of] the central Drum”; English text (edited from Portuguese):

“The

freestanding sculpture in polychrome wood, dedicated to the Saints and Doctors

of the Church[,] is by Olivier de Gant and Fernão Muñoz, from between 1511 and

1514.“Two [guardian] angels can be found between the central canopies.”

10:48 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Round Church, inside central drum; at left is sculpture of Apostle John

with the Virgin Mary looking up to Christ on the cross.

MT 10:56 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – another arch of central drum of Round Church.

10:47 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – sign for “Iconographic programme of the ambulatory” of the Round

Church, in English and Portuguese; English text at left (blurred, but mostly

deciphered [and edited] from the clearer Portuguese):

“At

the beginning of the 16th century the former Templar church became a chancel

with an ambulatory. Its iconographical programme is reminiscent [Portuguese:

evokes the image] of [a] New Jerusalem.“The [mural?] painting altar depicts the Life of Jesus. As the author is unknown, it is attributed to the Master of the Charola in [Portuguese: of] Tomar, Jorge Afonso (?), c. 1510-1519.

“The freestanding sculpture [Portuguese adds: of the vault] [,] dedicated to the Minor Prophets[,] is attributed to Olivier de Gant and Fernão Muñoz, from between 1511 and 1514.

“The mural painting that can be seen higher up represents the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, c. 1510-1515.

“At the [lower] level, in the cycle dedicated to the Life of Saints[,] is St. Anthony preaching to the fish by Gregorio Lopes, 1536-1539 and St. Bernard, attributed to Simão de Abreu, c. 1575.”

Callouts (labels) in Portuguese and English; English [edited per Portuguese]: At top (left to right): Shield [coat of arms] and Crown of Portugal; Crucifixion, Resurrection; Flight to Egypt, Christ and the Centurion; Entry of Christ into Jerusalem, St. Anthony Preaching to the Fish; Jesus among the Doctors in the Temple; Ascension of Jesus.

At bottom (left to right): Sophonias [Greco-Latin form of Zephaniah]; Resurrection of Lazarus, Joel; Zachariah, St. Sebastian photo [Portuguese: photographic reproduction]; Amos, St. Bernard; Baroque Chapel.

10:49 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Round Church, ambulatory with statues of minor prophets.

10:50 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Round Church – sign for “Freestanding sculpture at [Portuguese: of] the

central Drum” in English and Portuguese; English text at left (blurred but

deciphered from clearer Portuguese):

“The

freestanding sculpture in polychrome wood, dedicated to the Saints and Doctors

of the Church, is [Portuguese: was created] by Olivier de Gant and Fernão

Muñoz, from between 1511 and 1514.”Callouts (labels) in Portuguese and English; English [edited per Portuguese] at top (left to right): St. Paul; St. Basil; St. Anthony; St. Jerome.

At bottom (left to right): St. Augustine; St. Dominic; St. Peter.

10:50 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – view from inside drum of Round Church (with statues of saints Basil,

Dominic, Anthony, Peter, and Jerome on columns), and through arch opening in

west wall toward Coro Alto (High Choir) with round window.

10:52 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – view from Round Church, across the nave (on other side of near rail),

to Coro Alto (High Choir) from below.

10:48 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – view of Coro Alto (High Choir) from Round Church, showing more of

vaulted ceiling.

10:52 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – sign for “Igreja (Church)” with call-outs and text in English and

Portuguese; English text (edited from Portuguese):

“The

Church of the Convent of Christ is made up of:“the Charola or rotunda, dating from the 12th century – an early Templar Romanesque fortified oratory inspired by the Temple in Jerusalem. The capitals on the central columns and the painting on stone allusive of St. Christopher date from that period.

“the main body of the church – built in the Manueline style from 1510-15 by Diogo Arruda and João de Castilho. This body, which includes the nave, the upper choir and the lower choir, was joined to the Charola by means of an arch opened in the walls of the old oratory. The inner drum would be turned into a chancel.

“Between 1510-15[,] King Manuel also commissioned the decorative interior of the Church, adding stucco, carved woodwork[,] and fresco and secco paintings.

“From that period are the wooden statues in the chancel and also the upper choir stalls, now gone, by the Flemish sculptor Olivier de Gand and completed by Fernão Munhoz, and also a set of monumental wooden boards [Portuguese: tábuas (panels)] executed by the royal painter Jorge Afonso.

“The paintings on the peripheral altars of the Charola, by Gregório Lopes (1536-38)[,] would also be added during the 16th century, as well as the decoration on the triumphal arch by Domingos Vieira Serrão and Simão de Abreu (1592-97).”

English text of callouts (labels) of diagram at top left: At top left: Upper Choir. Between the two diagrams, from left to right: Church Main Body; Charola. At lower left, from top to bottom: Nave; Lower Choir; Manueline Window.

Having

already seen the Coro Alto (High

Choir) from the Charola below, we then went up stairs to see it more fully, although

it was roped off.

10:53 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Coro Alto (High Choir) with choir stalls (not the originals) and circular

window (which can be seen from outside above the Manueline window).

During the administration of

Henry the Navigator (first half of 15th century), a Gothic nave was added to the west side of the old Templar Charola (Round

Church) of the Convent, thus turning the Round Church into a church apse. From

1510 onwards, King Manuel I ordered the rebuilding of the nave in the style of

the time, which would later be named Manueline after him. Thus, this is known

as the Manueline nave. Its

construction, between 1510 and 1513, was under the direction of Diogo de

Arruda.

From the outside, the rectangular

nave is covered by abundant Manueline motifs, including gargoyles, Gothic

pinnacles, statues, and “ropes” that remind of the ones used on ships during

the Age of Discovery, as well as the Cross of the order of Christ and the

emblem of King Manuel I, the armillary sphere.

In the interior, the Manueline

nave is connected to the Romanesque Round Church by a large arch. The nave is

covered by beautiful ribbed vaulting.

In the Manueline building

campaign of 1510-1515, Dom Manuel was also responsible for commissioning a two-level choir at the west end of the

nave.

The Coro Alto (Upper Choir, High Choir) is a fabulous Manueline work,

with intricate décor on the vaulting and windows. The Coro Alto was built in

1510-13 by Diogo de Arruda, at the behest of Dom Manuel. It originally had

remarkable Manueline choir stalls installed by the Flemish sculptor Olivier de

Gand, but unfortunately they were destroyed in 1811 by Napoleonic troops who

occupied the Convent during the French invasion. (The lost stalls were later

replaced by the present ones, which came from the Convent of Santa Joana in

Lisbon.) The ribbed vaulting, by Arruda’s successor João de Castilho, unites

the High Choir and the nave; at the junctions of the ribs are three

characteristic symbols of the Manueline style: the Cross of the Order of

Christ, the armillary sphere, and the royal coat of arms. Under the High Choir,

is the Coro Baixo (Lower Choir), a

room that used to be the sacristy of the church.

The work on the church would be

completed in 1515, under a second contract with João de Castilho in charge;

this included the completion of the Manueline choir, as well as the dome of the

new church and the creation of a new and monumental portal of access to the

church. The main western doorway into the nave is a splendid example of Spanish

Plateresque style.

As

we came back down from the Coro Alto (High Choir) to cross the nave at the

level even with the floor of the Round Church, we might have missed the Coro Baixo (Lower Choir), if the attendant

who validated our tickets at this point had not pointed it out to us. He said

that important papers were signed and men joined the Order in this room; he

said it also had great acoustics. We had to go down some stairs to reach it. It

was a large room with a low, vaulted ceiling, below the High Choir. We were

free to walk around in it; only the area immediately around the window was

roped off (this is the inside of the famous Manueline window).

10:56 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Coro Baixo (Lower Choir), viewed from nave at level of Charola floor.

The Coro Baixo (Lower Choir), directly under the High Choir, initially functioned

as the sacristy of the church and was later called the Casa do Capítulo (Chapter

House). Its west window is the famous Manueline Chapter House Window.

10:57 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Coro Baixo (Lower Choir) – MT in that vaulted room, trying out the

acoustics and heading for Manueline window. Where the ribs of the vault

converge, there were Crosses of Christ.

10:58 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Coro Baixo (Lower Choir) – Cross of Christ at junction of ribs of

vaulted ceiling (mild telephoto 35 mm).

10:58 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Coro Baixo (Lower Choir) – Cross of Christ at junction of ribs of

vaulted ceiling (telephoto 64 mm).

Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de Cristo – diagram showing location of

the Charola and (to west) the Manueline church, both highlighted in yellow (pt.wikipedia.org).

From

outside the church to the west, we had a view of the west façade and the Manueline Chapter

House Window.

11:01 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – west façade with top of Manueline Chapter House Window and circular

window of Coro Alto above it.

The west façade is divided by two string courses of knotted ropes. The

round angle buttresses are decorated by gigantic garters (alluding to the

investiture of Manuel I into the Order of the Garter by the English King Henry

VII). The most outstanding features of this façade are the Manueline Chapter

House Window and the smaller oculus (circular window) of the Coro Alto above

it. The buttresses that flank these windows also include allusions to the tabuleiros of the Feast of Trays.

Tomar: Convento de Cristo – the oculus (round window) and elaborate pinnacles atop the western façade of the church (en.wikipedia.org).

11:16 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – west façade of Church with Manueline Window and oculus.

11:01 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Manueline Chapter House Window (view from right).

The so-called Janela do Capítulo

(Window of the Chapter House) was

created between 1510 and 1513 by Diogo Arruda, who also worked on the Belem

Tower of Lisbon, another Manueline masterpiece. This huge window in the western

façade is one of the most extraordinary achievements of the Manueline style,

with its emphasis on hyper-realistic, naturalist motifs, and is probably the

most famous part of the Convent. It bears most of the typical Manueline motifs:

fantastic and unprecedented elaborations of twisted ropes, corals, and vegetal

motifs. Symbolizing the Tree of Life or more likely the Tree of Jesse,

according to themes from the Bible, its iconography mirrors the “imperial”

program of King Manuel I and the Order of Christ and the maritime prowess of

Portugal. A plethora of maritime motifs are gathered around coral-encrusted “masts”

and rise from the carved roots of a cork tree, with rope motifs abounding.

Topping the window is the royal coat

of arms and the cross of the Order of Christ. Armillary spheres, the personal

symbol of Dom Manuel, appear at the upper left and right corners.

A human figure at the bottom of

the window probably represents the designer, Diogo de Arruda; however some

sources say it is “the old man of the sea” and others see it as the head of a

sailor upon algae mixed with rope, as a tribute to sailors (navegadores = navigators) that allowed

this greatness.

Once termed the most stupendous

creation of all times, this window has been used as yet another metonym for

Portugal.

It echoes the transition

between the two royal houses evoked by two turrets decorating the corners of

the nave (the left for the medieval epoch that is ending, the right for the new

epoch that takes over).

The window is best seen from the

adjacent Claustro de Santa Bárbara (Cloister of Saint Barbara).

11:17 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Manueline Window (view from left) (telephoto 76 mm).

11:00 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – sign for Manueline Window (Janela Manuelina) in English and

Portuguese; English part:

“The west façade window of the Convent Church

is attributed to Diogo de Arruda and was executed between 1510 and 1513.“It is one of the most singular examples of the late Gothic ‘Manueline’ style, with its emphasis on hyper-realistic, naturalist motifs. Symbolizing the Tree of Life or the Tree of Jesse, according to the themes of the Scriptures, its iconography mirrors the ‘imperial’ programme of King Manuel and the Order of Christ.”

Leaving

the church, the tour went westward into the Renaissance cloisters.

Having previously worked on the Convent

in 1513-1515, the architect Jo

returned for a second period (1533-1552),

inspired by the classical motifs of the Renaissance still visible in remnants

of his original Claustro

Principal (Main Cloister) and in the other cloisters to its north and west.

Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – diagram of 5 cloisters to west of church: Claustro de João III (blue);

above it the small Claustro de Santa Bárbara (pink); the other 3 Renaissance

cloisters (also pink) (pt.wikipedia.org).

The overall layout of renewal and Renaissance expansion by João de Castilho followed a rational (and functional) concept. Two long corridors in a cross articulate four main cloisters, which together form a huge quadrilateral. They are the Claustro Grande (Grand Cloister) or Claustro de João III (Cloister of John III), originally called Claustro Principal (Main Cloister); the Claustro da Hospedaria (Cloister of the Inn); the Claustro dos Corvos (Cloister of Crows or Ravens); and the Claustro da Micha (Cloister of Micha). (See separate notes below for more information on these four cloisters.)

A fifth cloister of more modest

dimensions, was originally called the Claustro Pequeno (Small Cloister), but

later renamed the Claustro de Santa

Bárbara (Cloister of St. Barbara). It was the first to be constructed (ca. 1531-1532),

and its stylistic characteristics signaled a radical break from the

hyper-decorative density of the Manueline and the choice of a new classicist

style. It came to occupy a key place of transition between the old and new

buildings. It was designed by the architect João de Castilho and served as a

distribution area. The central position of the Small Cloister allowed it to

distribute access to all parts of the Convent.

However, since it was attached to the

west façade of the Manueline church, it seriously affected visibility of the

façade. Therefore, the upper floor of the two-story cloister was demolished in

1843 in order to restore visibility of the west façade of the Manueline church,

in particular of the famous Manueline Chapter House Window. The window and the

west façade are now clearly visible from this cloister. The remaining, lower

floor of this cloister is covered with a ribbed vault and has 4 arched

supported by columns. The second floor is without cover; however, it still has

columns.

Tomar: Convento de Cristo - Sign for Claustro de Santa Bárbara (Cloister of

Saint Barbara) showing its location (commons.wikimedia.org). Text in English

and Portuguese; English text (edited per Portuguese):

“The

construction of the Small Cloister [Portuguese: Claustro Pequeno], as it was

first known, started in 1531 under [Portuguese: during the campaign of work of]

the architect João de Castilho; from that time it would provide access within

the Convent [Portuguese: it functioned as a distribution space into the

interior of the Convent].“In 1843, by order of King Fernando II, the upper floor was demolished in order to allow more space for [Portuguese: in order to clear obstructions (of view?) to] the Manueline Window.”

First,

we came to the Claustro de João III

(Cloister of John III), the largest of the Renaissance cloisters.

10:56 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Claustro de João III (Cloister of John III), S and W sides, with

fountain (above balustrade in shape of Templar cross); in far corner is one of

the spiral staircases connecting the two floors of the cloister.

The Claustro de João III (Cloister of John III), also known as Claustro Grande (Great Cloister) or Claustro Principal (Main Cloister), is

the most impressive of the Renaissance cloisters. It was started in 1533 under

King João III of Portugal and finished during the reign of Filipe I of Portugal

(also King of Spain as Philip II) in 1591.

Adjacent to the convent church,

the Claustro de João III flanks the southern façade of the Manueline nave. It

is actually two cloisters in one. It has two floors topped by a balustrade. This

magnificent 2-story cloister connects the dormitory of the monks to the church

and is considered one of the most important examples of Mannerist architecture

in Portugal. The stories are connected to each other by four elegant spiral

stairways, located at each corner of the cloisters. The courtyard has a

fountain in the center, in the form of the Cross of Christ. This Renaissance cloister

stands in striking contrast to the flamboyance of the monastery’s Manueline

architecture.

João de Castilho (1470-1552), who

was born in the Kingdom of Castile (now Spain) but settled in Portugal in 1508,

is considered the greatest Portuguese architect of the 16th century. When he returned for a second

period of work on the Convento de Tomar (1533-1552), inspired by the classical

motifs of the Renaissance, one of his first projects was the original Claustro

Principal (Main Cloister).

However, the original Main

Cloister was almost completely dismantled after the death of João de Castilho

in 1552, for reasons that remain unclear. João III, who had commissioned the

work of Castilho, then ordered its partial destruction, and it was replaced by

the remarkable Mannerist version of Diogo de Torralva. It reflected the

Mannerist style of the Italian Cinquecento (1500s, the Second Italian

Renaissance) and is considered a masterpiece of the architect and of European

Mannerism. It is arguably Portugal’s finest expression of that style: a somber

ensemble of Greek columns and pillars, gentle arches, and sinuous, spiraling

staircases. Thus, its design is different from the rest of the convent’s

Castilian architecture (named for the architect João de Castilho).

After the death of Torralva (in

1566), construction would continue under other architects (including the graceful

fountain, the work of Fernandes Torres, fed by the water of the convent’s

aqueduct).

Later work was added by the

Italian architect Filippo Terzi (1520-1597), who was active in Portugal at this

time. (This cloister is sometimes called the Claustro Filipino, which may

allude to the architect or more likely to the fact that it was completed during

the reign of Filipe I.)

Tomar: Convento de Cristo –

Renaissance Cloister of John III, ambulatory (pt.wikipedia.org).

11:03 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Claustro de João III (Cloister of John III), N and E sides, with

fountain (with clearer view of balustrade in shape of Cross of Christ around

fountain); in far corner is another of the spiral staircases connecting the two

floors of the cloister; the top of the Charola is visible in background.

11:03 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Claustro de João III (Cloister of John III) – MT on one of the spiral

staircases as we went up to the upper floor of the cloister.

11:04 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Claustro de João III (Cloister of John III) with fountain in center

and spiral staircase in far corner, (horizontal) view from upper level of

cloister; now the top of the Manueline nave and more of the top of the Charola

is visible in background.

11:06 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Claustro de João III (Cloister of John III), N and E sides, with

fountain in center and spiral staircase in far corner (with two people on

steps), (vertical) view from upper level of cloister; now the top of the

Manueline nave and a bit of the top of the Charola is visible in background.

11:08 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Claustro de João III (Cloister of John III), N and E sides, with

fountain in center and spiral staircase in far corner, viewed from balustrade

on roof of cloister; now the top of the Manueline nave and even more of the top

of the Charola is visible in background (vertical).

11:08 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – top of Manueline nave and Charola viewed from roof of Claustro de

João III cloister.

11:00 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Manueline window on south side of church, viewed from lower level of

Claustro de João III.

The Manueline Chapter House

Window on the west façade is probably Portugal´s most striking piece of Manueline

architecture. Unfortunately obscured by the Claustro de João III is an almost

equivalent window on the southern side

of the church.

11:11 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Claustro de João III (Cloister of John III) – MT going back down the

spiral staircase.

Unfortunately, the

marked tour route did not take us into all of the Renaissance cloisters. In particular, we missed the Claustro da Hospedaria and Claustro dos Corvos. We would later pass by the Claustro de Micha (see later notes.)

The Claustro da Hospedaria (Cloister of the Inn or Hostelry Cloister)

was designed to welcome visitors to the Convent and, therefore, has a noble

appearance. It was built between 1541 and 1542 to provide lodging for guests,

with the people of higher social status on the upper floor and the servants,

stables, and infirmary on the ground floor. It preserves features identical to

what might have been the original Grand Cloister of Castilho. Quadrangular

buttresses are in rhythm with the entire height of the cloister. It is covered

with ribbed vaults, and the ground-floor of the galleries consists of four

bays, with a double arcade based on columns with large capitals. The upper

floor is covered by wooden beams with caissons, forming an architrave with an Ionic

column in the center. The west side of the cloister has an additional floor,

identical to the first [US second] floor. The formal balance of this cloister

was seriously disturbed by the demolition, on the south, of the upper floor

gallery (for the same reason that dictated the amputation of the Claustro de

Santa Bárbara) and the addition, on the north, of an ungainly body called

Portaria Nova (New Gate), which distorts the balance of this façade.

Tomar: Convento de Cristo –

Renaissance Cloister of the Inn, west and north façades (pt.wikipedia.org).

The Claustro dos Corvos (Cloister of Crows or Ravens) and the Claustro da Micha (Cloister of Micha) are organized basically similar to the Claustro da Hospedaria, but they have a smaller scale and a simpler level of finish, since both are in functional areas intended for the novitiate and servants.

The Cloister of the Crows dates from the 16th century and was used for prayer

and reading.

Tomar: Convento de Cristo –

Renaissance Cloister of the Crows, façade (pt.wikipedia.org).

Tomar: Convento de Cristo

– Renaissance Cloister of the Crows, vaulted ambulatory (pt.wikipedia.org).

Then

we entered the Dormitório Grande

(Main Dormitory) of the Convent.

11:12 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – sign for Dormitório Grande (Main Dormitory) in English and Portuguese;

English text (corrected from Portuguese):

“Finished

between 1543 and 1545. It has 40 cells along the so-called crossing corridor,

consisting of three arms of identical size along the cardinal points. In the

southern arm, the lavabo [lavatory, washroom?] marks the completion of the

water supply to the Convent (1617).“The [wainscot of] azulejo tiles date[s] from the 17th century.”

11:12 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de Cristo

– azulejo tile wainscot in dormitory

corridor.

11:13 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – MT in long dormitory corridor with

azulejo tile wainscot.

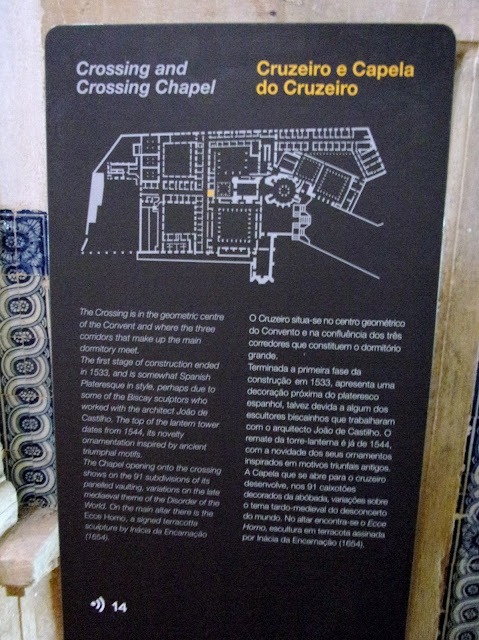

11:14 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – sign for Crossing and Crossing Chapel (Cruzeiro e Capela do Cruzeiro)

in English and Portuguese; English text:

“The

Crossing is in the geometric centre of the Convent and where the three

corridors that make up the main dormitory meet.“The first stage of construction ended in 1533, and is somewhat Spanish Plateresque in style, perhaps due to some of the Biscay sculptors who worked with the architect João de Castilho. The top of the lantern tower dates from 1544, its novelty ornamentation inspired by ancient triumphal motifs.

“The Chapel opening onto the crossing shows on the 91 subdivisions of its panelled vaulting, variations on the late mediaeval theme of the Disorder of the World. On the main altar there is the Ecco Homo, a signed terracotta sculpture by Inácia da Encarnação (1654).”

We

could not enter the Crossing Chapel

(Cruzeiro e Capela do Cruzeiro), but Don took photos from corridor.

11:20 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Crossing Chapel, Ecce Homo statue on main altar.

11:21 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo –

Crossing Chapel, to right of Ecce Homo statue on main altar; figures in

vaulted ceiling; azulejo tiles on

walls.

11:21 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Crossing Chapel, to left of Ecce Homo statue on main altar; figures in

vaulted ceiling; azulejo tiles on

walls.

11:23 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – view from corridor into one of the cells in the Main Dormitory.

After

touring the Main Dormitory, we came back to Claustro de João III and then to

the Refeitório (Refectory) in the

wing of the dormitory next to that cloister.

11:26 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – another view of Claustro de João III with fountain in courtyard.

11:26 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – sign for Refeitório (Refectory) in English and Portuguese; English

text:

“Built

by João de Castilho during the great campaign of King João III, and probably

finished between 1535 and 1536, according to the inscriptions on the pulpits,

reserved for reading during mealtimes. Note the perspective of the vaulting

ribs.

“The

antechamber has served as a pantry and gave access to the kitchen.

“The

wine and olive oil cellars lay below the refectory, as did other rooms of

agricultural nature, connected to the orange grove (Friars’ Garden) and the

Convent enclosure.

“The

present arrangement of the tables was due to later work, from the time of the

Seminário das Missões (Missions Seminary, 1922-92).”

11:26 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo –

Refectory, with pulpits on both sides for readings during meals.

The Refectory was built between 1535 -1536, again by João de Castilho.

Here the friars would have taken their meals in a room naturally cooled by the

thick stone walls. An anteroom connects the Refectory to the kitchen.

On

the way to the exit, we passed the Claustro

de Micha.

11:28 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Claustro de Micha - ambulatory and courtyard.

The Claustro de Micha (Cloister of Micha) was finished between 1543 and

1550. Its name originates from the bread leftovers that were distributed to the

poor who came here to beg.

11:35 AM – Tomar: Castelo de Tomar/Convento de

Cristo – Tabuleiros crown near exit.

We

got carimbos at the Castelo exit.

Just outside the exit, we bought figs and bananas from a vendor with a cart.

12:00 noon – Tomar: view of city from near exit of

Castelo de Tomar/Convento de Cristo – Igreja de São João Baptista and Praça de

República in center.

12:00 noon – Tomar: view of Igreja de São João

Baptista (telephoto 90 mm).

Then

we went back down the hill to the Igreja

de São João.

12:10 PM – Tomar: ground-level view of Igreja de São

João Baptista with statue of Gualdim Pais in square at left.

12:26 PM – Tomar: Igreja de São João Baptista –

tower with quadrangular lower body and octagonal upper body.

12:26 PM – Tomar: Igreja de São João Baptista –

Manueline main door.

Then

we went to the Sinagoga de Tomar,

where we again got carimbos.

12:12 PM – Tomar: sign by entrance on outside of

Synagogue, in Portuguese and English; English text:

“The

synagogue was at the heart of the life of the medieval Jewish community, and it

served as a temple, assembly, court and school.“This rare example of medieval Jewish temples and pre-Renaissance art in Portugal was built in the 15th century.

“It was closed in 1486 by D. Manuel I who forced the Jews to convert.

“Samuel Schwarz acquired it in 1923 and later donated it when the Abraão Zacuto Luso-Hebraic Museum was created.”

12:23 PM – Tomar: Synagogue entrance.

12:20 PM – Tomar: Synagogue interior.

12:23 PM – Tomar: Synagogue interior; MT getting our

carimbos.

Tomar is best known for the remnants of an impressive

Templar fortress and a superb monastery, but less known is the Synagogue of Tomar, the oldest existant

Jewish prayer house in Portugal.

The Synagogue of Tomar features a white-painted plain

façade. The interior boasts a quadrangular main prayer room of about 8 m on

each side. The ceiling is supported by 4 pillars with 12 pointed arches in the

Moorish style much appreciated in the Iberian countries during the Middle Ages.

In the Sephardi tradition especially in Portugal, the 4 pillars symbolize the 4

mothers of Isræl (Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah), while the 12 arches

represent the 12 Tribes of Isræl. The synagogue has fascinating, nearly perfect

acoustics, brought about by clay jars sealed upside down and incorporated into

the walls in the four upper corners of the room—an ingenious traditional method

during the Middle Ages. The Torah scrolls are kept in a wooden cupboard. Old

stone carvings that apparently ornamented the original structure are exhibited

around the room walls.

In 1985 a second small room next to the main prayer

hall was discovered, partially below the current street level. This, it turned

out, was originally used as a mikveh—a

ritual bath. This room houses a treasure of artifacts, mostly ceramic bowls.

Also discovered was a well, half covered by a more recent wall, in the patio

next to the mikveh; its edge bears

deep cuts from ropes.

There must have been a Jewish settlement in Tomar

already during the early 14th century, as it is mentioned in an inscription on

a gravestone of a Rabbi Josef of Tomar who died in Faro southern Portugal in

1315. An official Spanish document issued in Zamora on October 26, 1475 by D.

Afonso V mentions the Jewish community of Tomar.

Many Jews lived in the Jewish Quarter of Tomar, which

was closed at nightfall by chains. These Jews, like those in Rome, had one

synagogue. It was ordered to be built in the middle of the 15th century (between

1430 and 1460) by Prince Henry the Navigator, who gave shelter to the Jews, who

had acquired some prominence there, and created the Judiaria or Judaria (Jewish

Quarter). The synagogue was located in the middle of the Jewish Quarter, on

what was later named the “Rua nova que foi judiaria” (the New street that was

the Jewish quarter).

Just after 1492, with the expulsion of Jews from

Spain, the population of Tomar was increased by Jewish refugee artisans and

traders. The very large Jewish community dynamized the city with new trades and

skills. Their experience was vital to the success of the new trade routes with

Africa.

The synagogue of Tomar was in use until 1496. Then,

King Manuel I “The Fortunate” of Portugal issued the Edict of Expulsion of the

Jews from Portugal, giving Jews the choice to convert to Christianity or to

leave Portugal by October 1497. Under pressure from the Spanish monarchy, King

Manuel I proclaimed that all Jews remaining in his country would be considered

Christians, although he simultaneously forbade them to leave. Jews were largely

undisturbed as nominal Christians, until the establishment of the Portuguese

Inquisition in 1536. Under persecution, wealthier Jews fled, but most of the

others were forces to convert.

In 1497 the synagogue of Tomar stopped being a house

of worship and was sold to a private person. It was sold again in 1516 and

converted into a prison serving the town and region, replacing an earlier

prison in the castle. The prison continued to function in the former synagogue

until the mid-16th century, when it was transferred to the city hall. An

Inquisition tribunal was established in Tomar in 1543, but its activity was

stopped in 1548. According to parish records of a local church in Tomar, it

seems that the former synagogue was used as a Christian chapel in the early

17th century, when it was referred to as Ermida de São Bartolomeu (Chapel of

St. Bartholomew). In the late 19th century, the building served as a hay loft.

The building was sold and resold several times, eventually to a grocer, who

used it as his warehouse. Finally, probably with the help of its then owner, it

was declared a National Monument in 1921. As a National Monument, it is unique

in Portugal, as a symbol of religious coexistence in Tomar.

Then came Dr. Samuel Schwarz (also spelled Szwarc,

1880-1953) a Polish mining engineer, who was in Portugal on his honeymoon at

the outbreak of WWI and could not leave Portugal. Schwarz dedicated himself to

restoring Jewish life in Portugal and at his own expense undertook the

restoration of the synagogue, which he purchased in 1923. Plans to transferring

the building to the State of Portugal could not be realized because of a lack

of funds. In 1939, Schwarz finally donated the property to the state, on the

condition that the Luso-Hebrew Museum be installed there. In return Samuel

Schwarz and his wife were granted Portuguese citizenship that protected them

during WWII.

The Museu

Luso-Hebraico Abraham Zacuto (the Abraham Zacuto Portuguese Jewish Museum) is named after Abraham Zacuto (c.1450-c.1522), a mathematician and the author of

the celebrated Almanach Perpetuum, published

in Leiria in 1496, which contains mathematical tables that were used by many

Portuguese navigators during the early 16th century and later. Zacuto was a

famous Jewish astronomer who made navigational tools for the explorer Vasco da

Gama and for a time served as the Royal Astronomer to King João II of Portugal.

The museum’s exhibits include different various

archaeological findings that attest the Jewish presence in Portugal during the

Middle Ages. Among numerous gravestones that form the bulk of the collection,

there is an inscription, dated 1307, from the former main synagogue of Lisbon,

and a second notable 13th-century inscription from Belmonte, upon which the

Divine Name is represented by three dots in rather the same manner as in the

Dead Sea Scrolls.

Then

we stopped at a café, probably A Rosa -

Café dos Artistas, in Praça da República and got sangrias for €1.50 ea.

12:27 PM – Tomar: cafés on Praça da República,

including A Rosa - Café dos Artistas, where we got sangrias; Castelo de Tomar

on hill beyond the square.

12:35 PM – Tomar: our sangrias and Camino credencial on table at café on Praça da

República.

We

tried to visit Igreja de Santa Iria

across the river Rio Nabão, but it was hard to tell it was a church, except for

a small sign on the door, which was locked. It was next to the Café Santa Iria

and the corner for Rua Santa Iria, which we followed toward Igreja de Santa María do Olival, which was

easy to find, but was closed between noon and 3 pm.

1:25 PM – Tomar: Igreja de Santa María do Olival and

separate tower.

The Igreja de

Santa María do Olival (Church of Saint Mary of the Olive Grove) was originally

built in Romanesque style in the second half of the 12th century and the early

13th. However, the current building is mostly the result of a reconstruction

carried out in the late 13th century in early Gothic style. The main façade has